Should amateur authors listen to writing experts? Not necessarily.

See that title? That’s the closest approximation to clickbait that my milquetoast soul can manage. Not a ballsy Stop listening to writing experts now! nor a strident Why I stopped listening to writing experts. Just the murmured apology of a challenge. How British of me.

We’ll come back to that title in a bit. For now, even draped in its wet blanket, I think it’s suggesting something mildly heretical.

Psst… wanna try my book?

Surely amateur writers should always listen to expert opinion?

In every field of human endeavour, that’s how transmission of knowledge works. Expertise flows downwards from the top.

And what could be more arrogant, more Dunning-Kruger, than an amateur who thinks he knows better than a seasoned pro?

Nothing, maybe. Nevertheless, my contention is that in some circumstances, expert writing advice can cause amateurs all sorts of problems. And the first big problem is how we define expertise.

The Big Guy in the Gym

The problem of defining expertise first occurred to me in the gym. I’ve been lifting weights since 1978, and I’ve seen countless changes in training styles, training gear and gym culture. One decade-spanning constant, however, is an assumption that’s made about the Biggest Guy in the Gym. You know, that guy with ‘muscles in places where most people don’t have places’.

Since physical culture began, the Biggest Guy has always been surrounded by fawning beta males, pumping him – so to speak – for his training secrets. The assumption is that Big Guy must be a training guru.

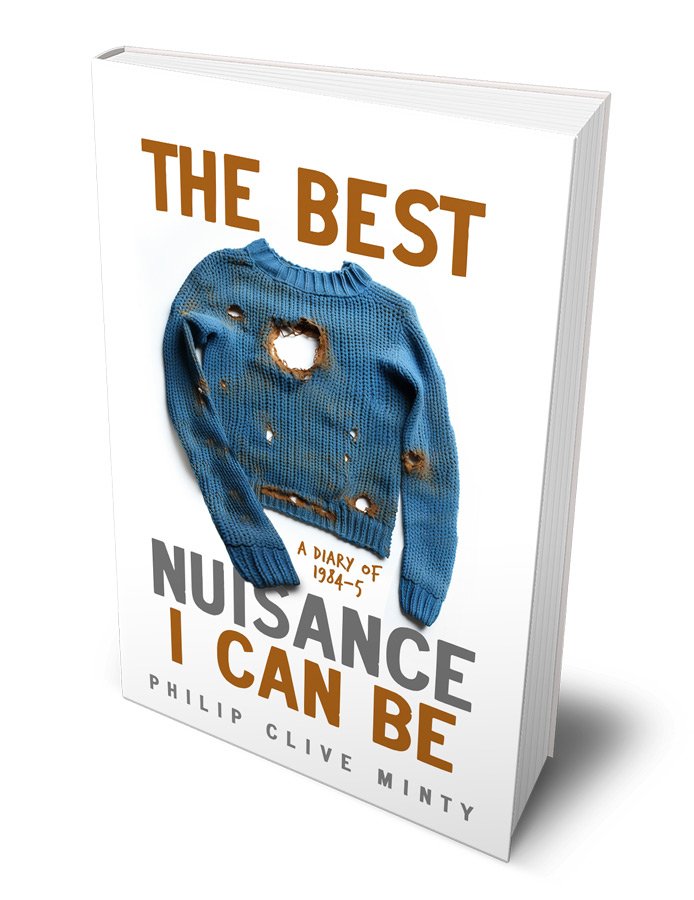

many moons ago.

For disguise explanation,

see ‘About’.

Yet careful observation of many Biggest Guys reveals that quite often, they don’t have a Scooby-Doo what they are doing. Their diet principles can include lashings of pseudoscience. Their training may be half-assed, dozy, counterproductive. “Well, it obviously works for him!” comes the refrain, but does it really? Or do some Big Guys succeed in spite of their muddled approach? Whisper this when the Big Guy is around, but his success may be more attributable to winning the genetic lottery, and a stellar response to exogenous testosterone.

The point is that we tend to conflate accomplishment with expertise. Getting back to writing, our measure of accomplishment tends to be book sales, and we assume that authors who have achieved decent sales must be experts from whom we can learn.

And when I say we, I actually mean me. Maybe you’re way too clever, but that was always my assumption about authorial expertise. Until, that is, I encountered DM.

The Strange Case of the Successful Illiterate

Sweet Jesus in a tumble drier, it was bad.

A while back, a friend put DM, as I’ll call him, in touch with me. DM had almost completed his debut novel, ready for self-publication on Amazon. My friend suggested that I could give it a quick once-over, telling me, “You might spot a few typos, stuff like that.”

DM thought this was a good idea and sent the file over.

Sweet Jesus in a tumble drier, it was bad. And I don’t mean the proto-fascist overtones or hackneyed story line. I mean that the guy couldn’t fucking write. On the first page, he’d made numerous grammatical errors, confused word meanings, got his tenses muddled up, and failed to convey what on earth was going on. It was almost unreadable.

I sent reams of feedback, couched as positively as I could, suggesting that the book needed a tad more work. I got a brief response thanking me, but concluding, “Think its [sic] mostly allright [sic] as is.”

I told my mate, in confidence, that DM couldn’t write for toffee and that he wouldn’t sell a single copy of his book.

Two years later, my mate apprised me of DM’s progress: “I think he’s sold a couple of thousand.”

Now, maybe my mate got the numbers wrong. I haven’t checked with DM. What’s certain is that he’s sold more than a handful, more than fifteen or twenty handfuls, and that alone is a profound mystery. If you have any clues, let me know. But I was left with a similar dizzying contradiction to the one I’d observed in the gym: by my standards, DM was an authorial success, and therefore a de facto writing expert. Yet I wouldn’t take his advice on writing a shopping list.

That Nice You Tube Lady.

You Tube Lady has sold more books than I ever will, and honestly, good for her.

Recently, I encountered a less extreme example of the accomplishment/expertise conflation. I started following a You Tube channel run by a young writer who is enjoying considerable success selling her Amazon-published books. As Amazon is the route I’m going, I was intrigued. Her optimism and enthusiasm are infectious.

In due course, I checked out her books. They certainly look the business, with eye-catching covers and compelling blurbs. I ordered the first in her series. It was a competent piece of writing. Plots and subplots progressed, characters were developed, conflict was engineered, tension was generated, and all within the framework of our current social mores. It was appropriate and nicely judged and bland and bloodless and awful.

You Tube Lady has sold more books than I ever will, and honestly, good for her. I mean it! I’m sure she’s worked extremely hard for her success, and she certainly is an expert in some areas of authorship. She’s wonderful at creating a buzz about her work, at connecting with her audience, at generating interactions between them. She produces accessible work that taps into something they want, and that’s part of authorship too. Just don’t tell me she’s an expert in writing, even though she proffers advice on that subject, and her thousands of followers recognise her as an authority.

She is an expert by several different metrics, but everything in the deep recesses of my soul tells me not to follow her expert advice.

What about advice from ‘proper’ writers?

OK, you’re right, there’s more than a little sniffiness and snobbery there. Also, I’ve picked two examples from towards the bottom of the literary food chain. So, what about advice from authors who have sold a gazillion copies and won critical acclaim?

My inexpert view is that their expert advice still should be treated with caution.

If that sounds perverse, consider the example of Kurt Vonnegut Jr. As an expert, he fulfils every criterion I could wish for. He was an undeniably important twentieth-century writer, a distinctive voice, a highly regarded stylist and he sold zillions of books. As a young man, I read his work obsessively. If I was to accept anyone’s advice, it would be his.

So, here’s a Vonnegut writing dictum, taken from his autobiographical work Palm Sunday:

Never include a sentence which does not either remark on character or advance the action.

Imagine that every writer before and after Vonnegut had used this principle. Bang goes two-thirds of Moby-Dick, for a start. Goodbye to vast swathes of Dickens and Tolkien. Bid farewell to your favourite authors’ rambling asides, their world-building, their lyrical descriptions that fulfil no other purpose than to be beautiful.

Even if you didn’t follow this advice literally, even if you just adopted its spirit, I’d argue that you would end up with a very particular sort of novel. You’d have a piece of work that’s focused and taut, and advances at a pleasing pace, and maybe has a sparse beauty to its prose. Perhaps one that sounded a bit like Vonnegut. And while I would love to be one-tenth as good as Kurt Vonnegut, I don’t want to sound like him, or even like a cheap knock-off.

Tentatively, I suggest that this applies to most pieces of writing advice. Propose a rule about any aspect of writing, and there will be a host of well-loved works that defy it. We’re admonished, for example, to develop believable, well-rounded characters. Yet dozens of wonderful books are peopled with absurd, two-dimensional cut-outs. Keep the narrative driving forward, we’re told. Yet some truly great works have long, boring sections where nothing much happens. Plot out your main dramatic and character arcs beforehand, say many. But a host of barnstorming authors are ‘pantsers’, who refuse to commit to even an outline before they begin.

And so on.

Even advice about work habits has the same potential flaw. The recommendation to have a regular writing routine seems completely sensible. It’s beautifully summarised in a phrase that’s been attributed to various authors:

“I only write when I’m inspired, and I see to it that I’m inspired at nine o’clock every morning.”

It certainly worked for me, helping me to build discipline and momentum. However, that doesn’t mean that it will work for you. Maybe you’re more like Ray Bradbury, who wrote Fahrenheit 451 in eighteen days, or Steven King who wrote The Running Man in a week.

Listen. Critically consider. Proceed with caution.

All of this sounds like I’m heading toward, ‘You have to find your own path, your own authentic voice. No one can teach you but you.’

Nah, that cannot be right. That’s got to be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

I think the contradiction is resolved if we think about two types of expert advice. The first is the generic sort we’ve considered so far, exemplified in that Kurt Vonnegut rule. In these cases, the appropriate response is to listen, thoroughly mull it over, consider how it applies to your own writing. Then, whether it’s a matter of process or style, character or pace, try it out. Once you’ve done all that, you may legitimately conclude that it is, or is not, useful for you.

However, there’s another category of expert advice: the sort that’s specific to your work. This might be, for example, feedback from a tutor, editor, ‘book doctor’, agent, publisher, or copywriter; someone who has both technical expertise and who knows your work (and what you’re trying to achieve). Even here, I wouldn’t throw critical consideration out of the window, and there may be individual battles to be had, but overall, that’s the advice I’m more inclined to follow.

Where does that leave us?

When I started writing this post, I wasn’t really sure what I thought about expert writing advice. Sixteen hundred words later, I think I can summarise where I am in three main points:

- For self-publishing authors, there’s a lot of ‘expert’ advice out there. I’m sceptical about a lot of this. In some cases, advice comes from people who are good at marketing rather than writing. In others, it comes from people whose writing, regardless of book sales, I wouldn’t wish to emulate.

- By necessity, writing advice from acknowledged luminaries is generic. It should always be thoughtfully considered, but not necessarily adopted.

- Specific professional feedback on your work is a different kettle of fish. You still shouldn’t accept it blindly, but rejecting it demands some damn good reasons.

If you’re brighter than me, which isn’t setting the bar very high, you’ll have figured this all out already.

Where do you stand on writing advice?

Agree? Disagree? Haddock?

Drop me a line with your thoughts, or let me know in the comments.