Long Review: A Picture of Dorian Gray

Oscar Wilde’s short bobby dazzler of a novel has lessons for today’s celebrity-obsessed world.

There used to be a common conversational trope, deployed to comment on someone’s youthful appearance. It went something like this, “You must have a picture of yourself locked in the attic.”

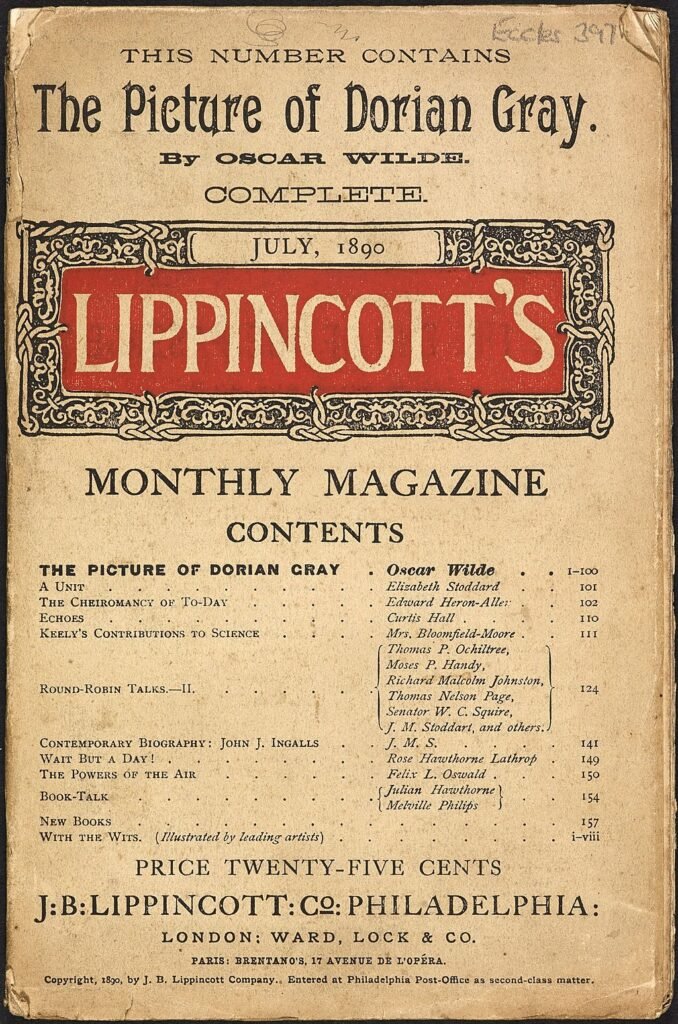

Though that particular idiom – like so many – has probably died peacefully by now, it demonstrates just how well-known Wilde’s 1890 novel has become. The story of an eternally youthful man and his hidden, decaying portrait has become embedded in our culture.

A Premise of Dorian Gray

Not completely spoiler-free, but you should be OK.

The novel’s plot is straightforward. Dorian Gray is a rich and physically beautiful young man. Whilst having his portrait painted, he meets a friend of the artist, Lord Henry Wotton. Lord Wotton is older, worldly, and specialises in sparklingly brilliant cynicism. Dorian immediately falls under his influence. Wotton argues that the cardinal virtue in life is beauty. He points out that age will gradually transform Dorian, ruining his perfection and turning him into a grotesque self-parody. Horrified, Dorian wishes that his portrait could bear the ravages of the world, while he remains unblemished. And being a fairy-tale, that is exactly what happens.

Wotton starts Dorian down a path of self-indulgence, hedonism and callousness. The now-hidden portrait (it’s never in an attic, though!) bears witness to his moral descent. By halfway through the novel, one could make a fair guess at its trajectory.

Bucketloads of themes

Plenty, I think. I’ve deliberately avoided reading any commentary on the novel, because for me, one of its principal joys was forming my own impressions – however misguided – and puzzling over what Wilde might be asking.

For example, take Lord Henry Wotton, surely one of the most subversive characters in fiction. Almost everything he says is wittily phrased, epigrammatic, eminently quotable. He appears to follow an alternative moral system, in which the only things of value are art, beauty and the pursuit of pleasure.

A good life, in this view, is one that is lived tastefully and artistically. He accepts this fearlessly and without reserve. In one episode, a young woman kills herself for love in a particularly ghastly way, and Wotton argues that this was the one act that redeemed her entire existence. Her suicide has ennobled her, elevating her worthless life to tragic status.

Intellect is in itself a mode of exaggeration, and destroys the harmony of any face. The moment one sits down to think, one becomes all nose, or all forehead, or something horrid.

So what exactly is Wilde doing with this character? Is Wotton a fin-de-siècle commentary on the transition to a secular age – one in which ideas such as soul and sin are about to become redundant? Is he a metaphor for Satan, tempting perfect and innocent Dorian with forbidden thoughts? Or perhaps Wotton simply enjoys saying outrageous things, and he is a symbol for how easily we all conflate wit with wisdom.

For me, questions like these pursued me throughout the novel and made it an unfailingly interesting read. Ambivalence is everywhere. The bouts of coruscating dialogue, for example, might have become too much of a good thing. But they didn’t, because I could never decide whether Wilde was showing off his genius, or satirising genius show-offs, or both.

Why read Dorian Gray?

One thing I loved about the novel is how, for a while, Dorian’s beauty protects him from accusation and condemnation (at least for a while). I mean, ain’t that the truth? We have a centuries-old culture of associating physical beauty with positive character traits. This ‘halo effect’ is a robust finding in psychological studies, but as usual, the novelists got there first.

In this, I see a link with our culture of influencers. We live in an age where the opinions of the beautiful and charming – or at least engaging – are followed by millions. Their views carry weight, not because these are profound, or insightful, or even necessarily factually correct, but because their celebrity lends a lustre to everything they say. In Dorian Gray, Wilde asks us why it is the surface, the outer characteristics, that continue to beguile us so much.

I did find Wilde’s treatment of social class hilarious. On the one hand, he reveals the contempt with which his aristocratic principals treat the lower orders. But on the other, he can’t seem to disguise his own horror at their vulgarity and beastliness. Much of Dorian’s fall into degradation seems to be due to him hanging out with the wrong sorts – in other words, the filthy peasants. And I therefore wonder if the novel sets us a presumably unintended question – how far can even a transgressive genius like Wilde escape their own cultural matrix?

One final question. Towards the end of the novel, Wotton quotes Mark 8:36, “…what does it profit a man, if he gain the whole world and lose his own soul?” From Faust to Citizen Kane, that’s a familiar enough theme. Wotton’s own response to the question, which I won’t reveal, encapsulates Wilde’s exploration of it – and it’s a dangerous, fascinating, masterful one.