Book Review: Captain Corelli’s Mandolin

Wildly and justifiably popular, Corelli has more themes than a lisping dressmaker (I’m copyrighting that!)

the person sitting next to you was reading this.

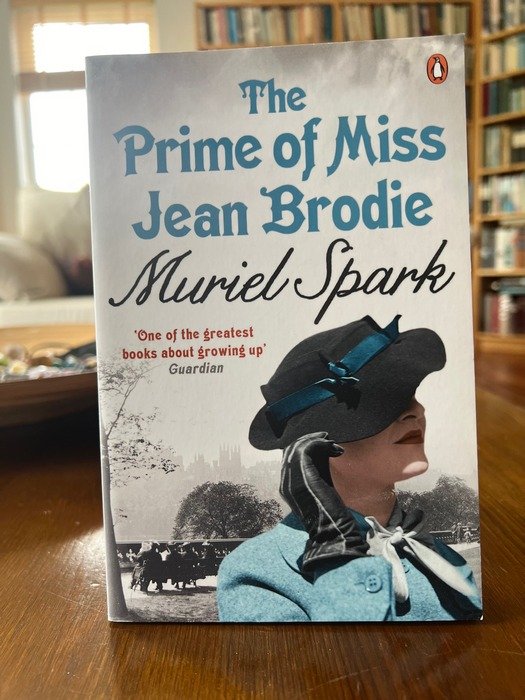

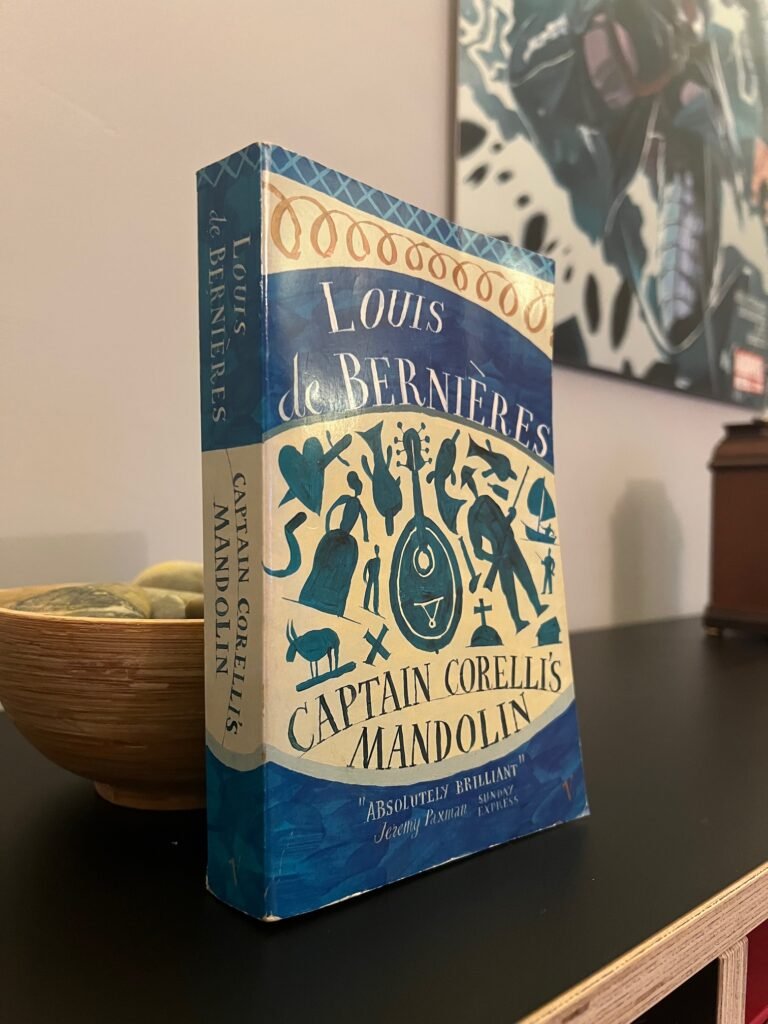

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin is a story of how war transforms all the lives it touches. It is also a story of enduring and unlikely love. The novel is set on the Ionian island of Cephalonia, and spans 60-odd years from an idyllic pre-war 1930s to the 1990s. Much of the action, and the central romance, is set against the backdrop of the WWII occupation of Cephalonia by Axis forces. A largely-forgotten war atrocity – the bestial slaughter of the Italian occupying troops by their former Nazi allies – provides a central element.

Captain Corelli was de Bernières’ fourth novel. He had previously won acclaim for his Latin American trilogy, but with Corelli, he hit the big time. The book was wildly successful, and for a while in the 1990s, every other person in the UK seemed to be reading it. In 2001, it was unhappily adapted for film, with the reliably useless Nicholas Cage as eponymous Corelli, and Penelope Cruz as Pelagia.

From sentiment to brutality (and back).

Captain Corelli is one of the most impossibly sentimental books I’ve ever read. And seeing as I am also impossibly sentimental, that meant I loved it.

From the first page, it seemed to me that de Bernières hit his stride with Corelli. I had read The War of Don Emmanuel’s Nether Parts and Senor Vivo and the Coco Lord, and whilst I enjoyed both, there was something unfinished about them. They were witty, knowledgeable, accomplished, but were burdened with too many bum notes. For me, the magic realist elements in both novels grated. Often. I also tried de Berniére’s Red Dog, but the less said about that, the better. Immediately, Corelli struck me as a more accomplished work.

Not that Captain Corelli is free from bum notes. Far from it. Louis is at his most tin-eared when he’s labouring a tragic contrast. He bludgeons us with his juxtapositions: an official account of a young man’s death with the horrifying real events; a glib Communist leader’s rhetoric with a ghastly execution. At these moments, de Bernières has the subtlety of a Las Vegas casino.

And speaking of horrifying realities, de Bernières has an apparently inexhaustible appetite for them, especially as they appertain to war. Again, sometimes he lays this stuff on with a trowel. Suppurating wounds, beshitted pants, shattered skulls and a panoply of diseases are described with punishing eloquence. In particular, his unflinching descriptions of murdered innocents can make Corelli a difficult read.

The selection box novel.

Yet if de Bernières’ ambition occasionally exceeds his grasp, that’s maybe because he is aiming so high. It must be exceptionally difficult to combine a traditional romance, a history, a comment on the follies of ideology, a war story, a study of how grand historical events intersect with the lives of the ordinary, a tragedy and a comedy. It has more themes than… but I did that one already.

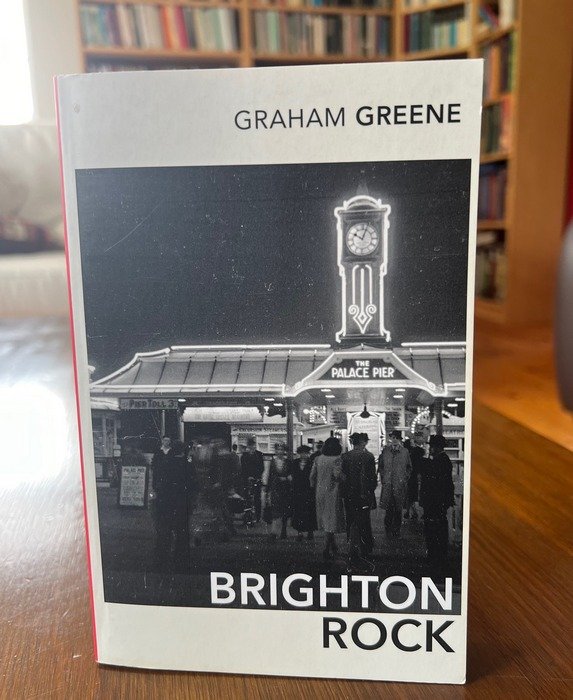

1970s Britain, you won’t get this joke.

Edwardx, CC BY-SA 4.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

And if it’s hard enough to write a selection box novel, offering something for everyone, it must be harder still to do it using a patchwork of interlocking narratives, many told in the first person. I’m full of admiration for anyone who attempts this. I think on balance he did a fine job. To write a love letter in the voice of a teenage girl, for example, takes some doing. Admittedly, Mussolini’s first-person rant had more than a whiff of Basil Exposition about it, but no one’s perfect.

A good novel leaves you wanting to discover more about the world in which it’s set. Corelli has made me yearn to read about Cephalonia, Mussolini, Communist partisans and WWII in Greece. Oh, and music theory. So I’m happy to say that Corelli”s spell is lasting beyond its pages.

Stereotypes. Soppiness. Superb.

In an age of cautious ambiguities, it was interesting to read a novel with broad national stereotypes and clearly defined villains. The British are lovably arrogant. The Italians are fun-loving, musical, party guys. The Germans are cold, orderly, obedient, humourless, unmusical – and villains to boot. The communist factions are the worst villains of all. More broadly, anyone who places an ideology above common humanity is off the de Bernières Christmas card list. De Bernières nails his colours to the mast, and if that results in a lack of nuance, it also makes for a spirited and passionate read. That fits with the novel’s prose style: Corelli is lushly, lyrically overwritten. Where there are some coolly ironic sections, there are far more that are positively dripping with juicy, lip-smacking tropes that de Bernières obviously had a ball writing.

As for the central romance, well that’s as soppy and unlikely as they come. Hard-hearted miserabilists will hate it. I loved it, and blubbed heartily at the long-delayed denouement.

The Verdict

Hey, don’t neglect this classic.

OK, calling it a classic might be a bit premature. But I reckon that my book is a pretty good read – for the right sort of person!

The Best Nuisance I Can Be is a novelisation of my real 1984-85 college diaries. It covers my tumultuous final year as an undergraduate at an English university, a period that delivered friendship, love, oodles of fun and some horrible self-discoveries.