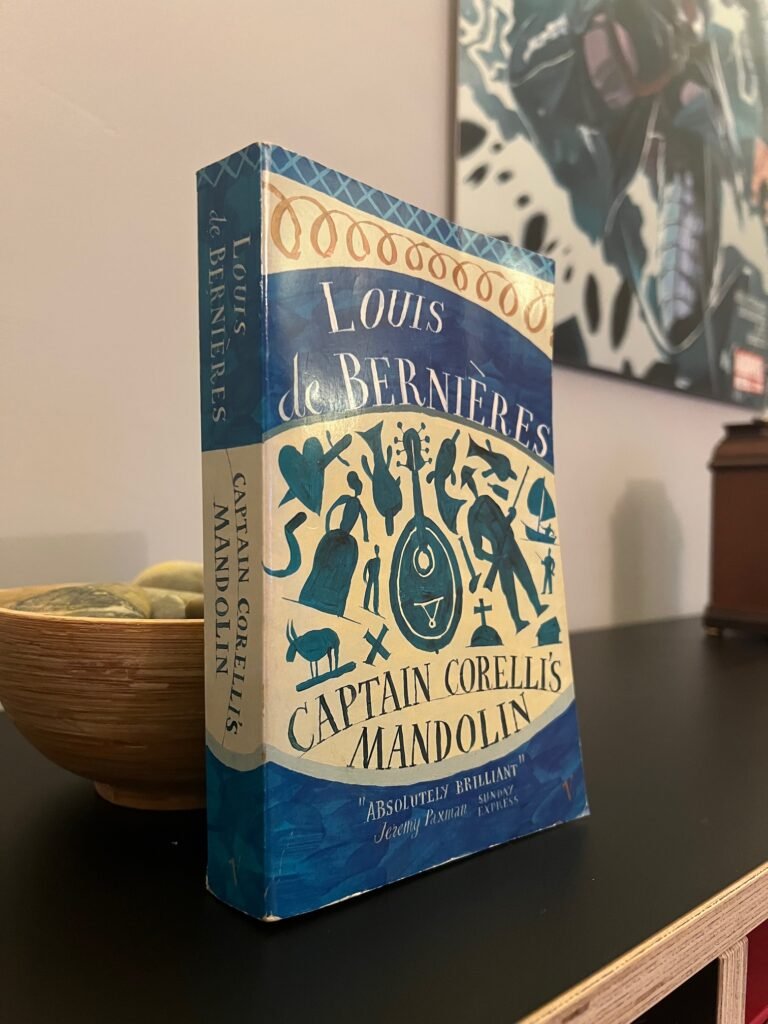

The Long Review: Brighton Rock

A review written for my mates, with plenty of swearing and spoilers.

A few years back, I tried to start a reading group with some mates, and we decided to tackle Brighton Rock. The shared experience just didn’t work out, but I wrote a book review anyway. I doubt that any of them had the patience to read it, but you might do better.

If you just want the short version, here we go:

Brighton Rock’s 250-odd pages cover a lot of ground, combining gangland thriller with a complex meditation on human nature, good and evil, Catholicism and social stratification. It’s not exactly light-hearted: the protagonist is a monstrous teenage sociopath and the setting is relentlessly squalid. But if you can cope the bleakness, it’s a satisfyingly grown-up, serious read.

Now onto the full-fat version…

Brighton: what a great setting.

Brighton Rock is a novel that manages to combine gangland thriller with explorations of class, poverty, sexuality, good and evil, and Catholicism.

As I haven’t done any background reading on the book, what follows are my own thoughts, which may well be completely wide of the mark.

To start with, I’ll pick up on [name omitted]’s comment, offered when 70% of the way through:

“thank fuck I wasn’t born in 1928.”

Yes indeed. In fact, one of my enduring memories of Brighton Rock is its portrayal of 1930s Britain as a squalid, dystopian toilet of a country. A place where 20th century innovations like motor cars and trolley buses cannot mask a persistent, brutally feudal class system.

To show us this grim bit of social history, Greene picks Brighton. It’s a fabulous choice, because on the one hand, there’s the picture postcard town so familiar to our grandparents: dances, warm-beer pubs and amusement halls, a bit of escape and harmless hedonism. But then, Greene flips the postcard over and there’s the other side, an everyday hell of grimy boarding houses and grinding poverty.

But although the social environment shapes the characters, BR isn’t simply a depressing tour round a shit country. It’s a proper and oddly cinematic novel.

Film noir thriller, now with added Catholicism

makes your eyes go funny.

FOTO:FORTEPAN / Magyar Hírek folyóirat,

CC BY-SA 3.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

I spent the first 20 pages of Brighton Rock not really understanding wtf was going on. That’s because the plot is gradually revealed through action and dialogue, rather than exposition. It made for a slightly uncomfortable beginning, but it was a good trade-off. It eliminated any clunky exposition at the start, and in fact that continues throughout. Brighton Rock is therefore firmly in the show-don’t-tell tradition. That’s something that cinema often does well, or even Netflix documentaries (have you noticed there’s almost never any narration?)

But what’s really quite odd is the combination of film noir elements – underworld murders, imperilled women, creeping menace – with big Catholic themes. So, for example, Pinkie and Rose are driven by notions of damnation and punishment. In fact, the plot is mainly a kind of framework on which to hang questions about good, evil and religion.

Can a thriller and philosophy lesson fit together? I think they did for me, because I wanted to know what was going to happen, how things would turn out and I was interested in the moral questions.

About that Catholicism…

The limits of my research were to discover that apparently Brighton Rock is one of Greene’s three ‘Catholic novels’. The others were Mary Magdalen Goes Apeshit and Nun for Me, Thanks.

As I’m not a Catholic, some of the ideas no doubt went over my head. Nevertheless, there was plenty that even an old atheist like me could pick up on. Catholicism defines everything about Rose and Pinkie, and also their relationship with one another. Other characters are shaped by their response to the faith. Ida’s blousy secularism, for example, is defined by its contrast with Pinkie’s other-worldly obsession with sin and hell.

Catholicism is even in the book’s title. Towards the end of the story, Greene makes the connection for us. Our true nature runs through us from beginning to end, just like the writing in a stick of Brighton rock. We can easily recast this in catholic terms: Man’s essential nature is sinful, and can only be redeemed through the intercession of the church. In other words, through confession and acceptance of Jesus through catholic ritual.

Both Pinkie and Ida seek escape from their nature and fate. Pinkie thinks that ambition will see him transcend and triumph over a destiny forced on him not only by God but also through the very human class system. Rose seeks redemption through love of Pinkie and faith in him.

Great big spoiler: in the gloomy conclusion, we learn that you can never escape your fate. The system is rigged, the damned stay damned. When Pinkie is splashed with his own acid, his screams and steaming flesh recall the effects of holy water on other cursed creatures, like demons and vampires. His psychological hell becomes physical. And it’s surely no coincidence that his life ends in a fall — like Lucifer cast out of Heaven, he has defied the order of the universe and paid the price. And a similar fate, metaphorically speaking, awaits Rose. The closing line of the book tells us that her faith in a false prophet will be punished by living damnation.

Ida vs Pinkie

For me, the best part of Brighton Rock was the conflict between Ida and Pinkie. From the opening pages, it’s clear that these two polar opposites will be on a collision course. They make fascinating adversaries, and Greene is perhaps asking, “What do good and evil look like in my world today?”

For 1930s Britain, ‘good’ turns out to be Ida, a sort of kindly hustler and good-time girl. Physically and psychologically, Ida embodies everything life-affirming: she is sensual, promiscuous, fond of drinking, laughter and nostalgic songs. Happily, her huge breasts are frequently mentioned and become a symbol for her formidable, thrusting presence, sexuality, and bounteous nature.

Ida is good, and yet not in the least religious. Her god is manifested in a vague spirituality that’s confined to Ouija boards. What she has instead is a concrete and real desire to be involved, to do the right thing. Thus she champions the friendless and hopeless Hale even after his death, seeking judgment of the guilty.

Pinkie is such an interesting contrast. He is closed to all earthly pleasures. He does not smoke, drink, gamble. He hates music and is disgusted by the idea of sex. So Pinkie is a paradoxically pure figure, driven by a higher calling – his ascent must not be compromised by these base temptations. Even his appearance reflects this rejection of fleshly enjoyment. He cuts a meagre figure, and again his pallid weediness contrasts against plus-sized sexpot Ida. In seeking redemption for his squalid beginnings, Pinkie has chosen the aesthete’s path.

So what are we to make of these two portrayals? Is Greene saying that religious denial just fucks you up, and the path to goodness is through being an essentially godless do-gooder? Hmm. Not so sure on the first one, but I think certainly we should say ‘not so fast’ on the second. After all, Ida is at least partly responsible for the death of Spicer and arguably for Rose’s eventual fate.

In fact, maybe Ida is a metaphor for our blundering attempts to do right without God. She is guided by empty-headed platitudes, convinced of her own moral rectitude and so she acts with good intentions but without understanding. Maybe Greene is saying that our busy-bodying interventions achieve little, but we’re too smug to even see it.

Anyway, for readers not interested in all this good-and-evil guff, I think the book has one more really interesting question. Which is…

Can we sympathise with Pinkie?

Obviously, at one level, that Pinkie, he’s a right prick. A violent sociopath, he manipulates and betrays others for his own gain, he has no empathy, and he enjoys inflicting pain. Wherever love and joy normally resides within humans, there is only hatred, and an aching need to subjugate.

He’s not likeable. You wouldn’t want to live next door to him. But is he to any extent sympathetic?

Here’s a young man, just a boy really, who is sneered at for his age, his origins, his cheapness. The viciousness of the British caste system means that he will always be denied power, opportunity and respect. He has seen his destiny — the world of his parents — an endless purgatory of squalor and debased animal carnality. And Pinkie’s not having it. He will seize the things he wants, which aren’t really all that much, through a brutal application of his will.

Another way of looking at Pinkie is that he’s a man on a do-or-die escape mission. He is a player from the Projects, fighting his way out.

What’s more, Pinkie stands alone. The rules of the game are enforced not only by his adversaries but also by his friends: they insist that he should drink, smoke, dance, have sex. They tempt him, inviting him to join the ranks of the well-adjusted. Pinkie refuses. Despite everyone, he pursues his own oddly puritanical vision. In another context, we might even call that admirable.

So, Pinkie is the serpent in paradise. God and the good old capitalist system have ordered the universe, and he is there to disrupt and spoil it. Pinkie is evil, from his narrow head to his cheap brown shoes, but he also a symbol of free will. That’s what makes him such a mesmerising character at the centre of a tough but absorbing book.

The Verdict

Hey, don’t neglect this classic.

OK, calling it a classic might be a bit premature. But I reckon that my book is a pretty good read – for the right sort of person!

The Best Nuisance I Can Be is a novelisation of my real 1984-85 college diaries. It covers my tumultuous final year as an undergraduate at an English university, a period that delivered friendship, love, oodles of fun and some horrible self-discoveries.