The Long Review: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

A very long review of quite a short book, with loads of spoilers.

I read Jean Brodie just after completing Nevil Shute’s On the Beach, which meant that I jumped from one strange book into an even stranger one. I’d also got quite the wrong impression about it, thinking it was a Mr Chips-style portrait of a devoted and much-loved teacher. Nothing could be further from the truth. This is a clever, dense, layered, short novel, replete with moral ambiguities.

Googling ‘The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie’, the suggested searches include: ‘What is the point…?’, ‘What is the irony in…?’, ‘What is the symbolism in…?’ along with the inevitable, ‘Is The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie based on a true story?’ My guess is that this gets set as an A-Level text, and you can see why. There’s so much to get your teeth into.

The Outline

Set in 1930s Edinburgh, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie recounts the stories of a charismatic schoolteacher – the titular character – and the girls in her charge. At the start of the novel, Jean Brodie has singled out a small group of her junior school pupils for special treatment. The ‘Brodie Set’ will be given a supplemental education that is out of kilter with the rigorous but conservative principles applied at the private school. The six girls meet regularly with Miss Brodie, often outside of school hours, and she instils into them her own values and beliefs. They become her acolytes and confidants.

Miss Brodie’s unconventional methods meet with the disapproval of the other staff, and especially that of the headmistress, who schemes to get rid of her. She pumps the Brodie set for information that may allow this, and especially for any details that might confirm Miss Brodie’s sexual misconduct. And this might have yielded results, as Miss Brodie is in love with the married art teacher and sleeping with the music teacher. However, loyalty of the Brodie set prevails and Miss Brodie continues her tenure.

As the girls mature and explore their own paths, Miss Brodie narrows her attention to two girls, Sandy and Rose. Her romantic love for art teacher Mr Lloyd continues, and she decides to possess him by proxy. She plans for Rose, now 17, to become his lover, whilst Sandy reports the progress of the affair. However, it is Sandy who embarks on an affair with Mr Lloyd. Having cast off Miss Brodie’s spell, Sandy encourages him to despise her former guru. And he seems to – and yet all of his portraits continue to resemble Miss Brodie.

During a meeting with the headmistress, Sandy tells her that although Miss Brodie has escaped being denounced for sex, her politics might serve just as well. This is because Miss Brodie has long been an admirer of the fascist movement. As events hurtle towards WWII, her sympathies are now sufficient to end her career.

We learn of the protagonists’ varied fates. Miss Brodie is crushed by her dismissal and dies in her fifties. Only at the very end of her life does she finally realise it is Sandy who betrayed her. Sandy becomes a nun and author of a celebrated psychological treatise; it is she whose recollections we have been reading.

The incurable romanticism of the fascist.

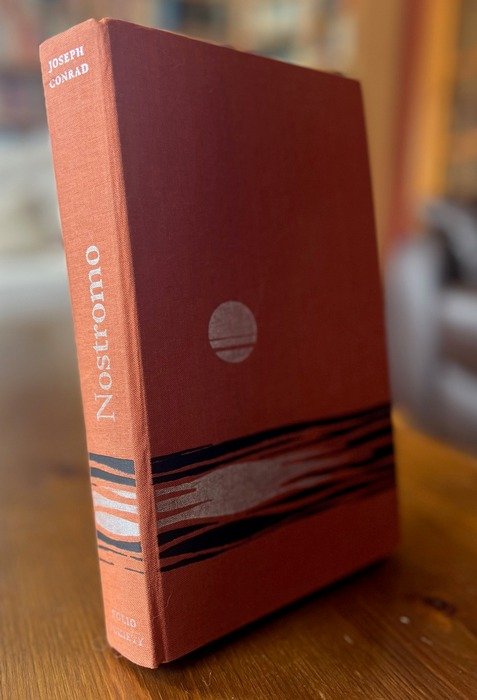

Fab portrait of a fab writer.

I’ve no doubt that Jean Brodie has several themes that I’ve entirely missed, and there are others I’m aware of but don’t feel qualified to discuss, so I’ll just mention two that interested me.

The first is fascism. Miss Brodie is an ardent admirer of Mussolini and the blackshirts, then later the Nazi brownshirts. She is also instrumental in causing the death of a pupil by persuading her to go off and fight for Franco. As noted, it is these leanings that lead to her downfall at the hands of her star pupil Sandy Stranger, who reports her advocacy to the headmistress. Sandy says that Jean Brodie is ‘a born fascist.’ I think Sandy’s right, but it’s a complex thing.

The context matters here. We now look at fascism through the lens of history. It’s impossible today, one hopes, to ignore exactly where fascism leads. But that wasn’t the case in the early 1930s. The fascists were an opposing force to Bolshevism, regarded as the principal threat to western civilisation. The fascist quest to root out degeneracy and restore traditional values, as well as to reinvigorate national pride, was one that chimed with many, including plenty of 1930s Tory MPs. Fascism was not universally looked on as a synonym for evil, it was just another competing ideology. As an example, consider the dazzling Mitford sisters: Unity was a fervent admirer of Hitler, Jessica was a communist, and Nancy thought it was all a frightful bore. Also, in the early days, it was easier to dismiss the reports of fascist thuggery and brutality, especially when the English believed that Johnny Foreigner was already prone to that sort of thing.

Like Brodie, fascists are fundamentally romantic: they are in pursuit of a romantic ideal.

It may seem odd that Jean Brodie, an advocate of such progressive ideas as sexual freedom and female empowerment, should be a fascist supporter. But I think her attachment to fascism goes deeper than that. Like Brodie, fascists are fundamentally romantic: they are in pursuit of a romantic ideal. Nazism is tied to idealised notions of purity, health and strength; their propaganda is filled with images of beautiful families. Hitler’s architectural plans were classicist. Mussolini too wanted a return to classical Rome. Fascist dictators pursue these ideals regardless of the human cost. The fate of individuals is secondary to achieving this higher vision. We see this in Miss Brodie’s imposition of her ideals on her set (whether these are a good match for those particular girls or not), in her attempt to seduce Mr Lloyd using her pupil Rose, and in the aforementioned encouragement of Joyce Emily to fight in Spain. And about that: one might anticipate that Miss Brodie might be traumatised by Joyce’s death, but far from it. Joyce has sacrificed herself for a greater cause.

What’s crucial, I think, is that Miss Brodie does not want to cause harm. She is not malevolent or sadistic. Indeed, she wants to raise her elect few to dizzying heights, for them to breathe the rarefied air that she does, to set them free. This too parallels the fascist dictators.

A fascist leader presents himself, or occasionally herself, as a saviour their people, the only person who can provide the answers and lead the elect from the wilderness. They do this through creating a cult of personality, shutting down dissent, and establishing themselves as the sole fount of knowledge and the sole arbiter of value. Insert comparison with your favourite populist leader here! We see Miss Brodie doing this throughout the novel. When her control is threatened by rival influences, in the form of new specialist teachers, Miss Brodie immediately belittles their subjects’ importance. She ranks the subjects in order of importance, placing those in which she cannot compete (such as Maths), at the bottom. What’s unspoken, but obvious, is that the most important subjects on the curriculum are the likes and dislikes of Miss Brodie.

Lastly, like a fascist dictator, Miss Brodie presents herself as a martyr, maybe even a Christ-like figure. She repeatedly tells the girls how she is sacrificing herself (her ‘prime’) for their sake. She seeks to convince them of her altruistic devotion, partly to inculcate gratitude and debt, but partly because she believes it to be true.

The warning is that fascism comes clothed in noble aspect and purpose. It can be magnificent as Jean Brodie’s profile, as uplifting as her eulogies on art and beauty.

One could argue that The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie both warns and consoles us regarding fascism. The warning is that fascism comes clothed in noble aspect and purpose. It can be magnificent as Jean Brodie’s profile, as uplifting as her eulogies on art and beauty. It is charismatic, too, drawing us in with charm and seeming infallibility. And yet, the novel consoles us with the knowledge that fascism can be stopped, and that its effects don’t last forever. In Miss Brodie’s case, her girls do not adopt her values. Some remember her fondly, perhaps, but has they move into adult life, her influence disappears.

Calvinism vs Catholicism

Disclaimer: I don’t know what I’m talking about on this one.

As I understand it, a central tenet of Calvinism is predestination. The fate of our immortal soul has been decided before we are born, and our good or bad deeds don’t affect that. God, in his infinite mercy, will consign all but the elect few into the fiery depths of hell for eternity. So why do good deeds at all? Because, say Calvinists, that is what we should want to do regardless of our fate. We should want to follow God’s plan, it’s our duty. This contrasts with the Catholic notion that both good works and faith are necessary for salvation.

The book mentions that God sometimes plants the false idea in the minds of the damned that they are in fact the elect. I think this originates not with the Calvinists but with St Augustine.

So, Miss Brodie could be seen as acting like the God of the Calvinists. There are a certain number of the elect that only she can choose and elevate by her will. The rest are condemned to the hell of mediocrity and remaining unilluminated by beauty. Further, we could say that this is nothing to do with merit. After all, Miss Brodie has chosen the very stupid Mary MacGregor, who can’t benefit from Miss Brodie’s education, whereas more deserving girls might have done so. If Jean Brodie selects meritocratically, it’s not by a system humans can discern.

There’s a nice irony in that Miss Brodie teaches the values of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, but unconsciously subscribes to the methods of the Calvinists.

The betrayal

The story turns on the betrayal of Miss Brodie by one of her favourites, Sandy Stranger. There’s a central mystery about why she does it.

One answer is that Sandy is acting out of a sense of duty and altruism. There would be ample grounds for this, given that Miss Brodie had inadvertently sent a girl off to her death in the Spanish Civil War. Sandy even tells the Headmistress that Miss Brodie must be stopped.

And yet, that doesn’t fit at all with Sandy. She becomes a cold, unpleasant character. Her small eyes symbolically seal her off from other people: she looks untrustworthy, and she is. Even the Headmistress, whom she is helping, doesn’t like her. Miss Brodie says that Sandy has ‘insight but no instinct.’ Is what she means by this that Sandy has no human instincts, no instinctive love? Furthermore, Sandy shows little interest in real people. She’s far more fascinated with orchestrating her fantasy world.

Perhaps her treatment of Miss Brodie is an extension of her need for control. As a young girl, Sandy constructs elaborate fantasies in which she plays a central role. Through her creative act, others play out roles that she determines. In Miss Brodie, she finds someone who can control and manipulate in real life. She commands the love of two men. She controls one sexually, against the social mores of the time. She bucks the school system, and she has real-life acolytes. Is Miss Brodie’s destruction a demonstration that Sadie can best Miss Brodie? First, she subverts Miss Brodie’s plan for Rose to become Mr Tully’s lover, then destroys her career, then seems coldly satisfied.

Is Sandy demonstrating that her model of the universe is the correct one? And to do this, is it necessary to prove that Miss Brodie is a false prophet?

Or is the betrayal a religious one? Sandy embraces Catholicism, and we’ve seen that Miss Brodie acts like a Calvinist. Is Sandy demonstrating that her model of the universe is the correct one? And to do this, is it necessary to prove that Miss Brodie is a false prophet? Does Sandy want to demonstrate, ironically, the truth of Augustine’s proposition, that some who believe themselves to be elect (which Miss Brodie certainly does) are actually damned?

Maybe it’s more to do with sexual jealousy and control. Mr Tully is having an affair with Sandy, and Sandy encourages him to despise Miss Brodie, to write her off as ridiculous. Disgustingly, he’s willing to do so. And yet, for all that, every portrait he paints looks like her. It’s that irresistible magnetism, perhaps, that Sandy has to stop.

Masterful ambiguity

I’m not sure that The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie is an enjoyable book, but it’s certainly a rewarding one. For such a slim volume, it gave me plenty to chew on. That’s reflected in the length of this review (now over 2000 words!).

I know that there are aspects of the book that went over my head. I’ve glanced at critical reviews and they have much to say about the structure and narrator, aspects that I barely noticed and which didn’t interest me.

What interested me more was the ambiguity of Jean Brodie. On the one hand, she’s a heroine for her age. She’s courageous and determined, one of those women in the vanguard of challenging a repressive society. And she does it with irresistible style, with her fine Roman features and haughty gait and memorable catchphrases. She’s devoted to art and literature. She sees education as going well beyond the mundane pragmatism that’s practised at the school, and is on a mission to introduce her girls to a wider and more beautiful world. She is a distillation of that teacher – the one with whom you felt a special connection, the one that you talked about and speculated on and never forgot.

The elevation of her crème de la crème, comes, one feels, at the expense of everyone else. It’s Nietzschean, anti-democratic and profoundly unfair.

Yet, there’s the other side of Jean Brodie. She forms a cult of personality, a sect which is founded on loyalty and devotion. I’ve already mentioned her attempts to embroil the girls in her proxy romance, attempting to persuade Rose, who is 17 or 18, to sleep with married Mr Tully. Also as noted, she encourages rebellious Joyce Emily to fight for Franco, leading to Joyce’s death. She colludes with her sect, involving them in adult school politics, and undermines the credibility of the other teachers. The elevation of her crème de la crème, comes, one feels, at the expense of everyone else. It’s Nietzschean, anti-democratic and profoundly unfair.

For all that, I’ve got more than a little sympathy for Jean Brodie. It’s not that she wants to do bad things. On the contrary. It’s just that she’s got her head so far up her own ass that she couldn’t countenance any possibility that she’s doing anything wrong. She has complete moral certainty and is defended against countervailing views by an impenetrable armour of superiority. After her defeat, she is whining, boring, shrunken. Her early death from cancer symbolises a soul consumed from within. It’s tragic to see her reduced from her glorious prime. That evokes the more universal tragedy for all of us – that of going downhill from that which we once were and will never be again.

A hideous little sneak, twisted by her intelligence and tiny-eyed ugliness into an envious and vindictive young woman…

The other fascination is narrator Sandy, another ambiguous figure. She stops Jean Brodie, and on balance that’s probably a good thing, but I find her revolting. A hideous little sneak, twisted by her intelligence and tiny-eyed ugliness into an envious and vindictive young woman, using her psychology and religion to analyse, and hence hide from, the messy imprecision of human interaction. And now I think I understand Miss Brodie’s ‘insight but not instinct’ comment. Sandy is a pontificating commentator, terribly good at finding the patterns and the flaws in the performance, but too afraid to have a go herself. Not for nothing is the ninth circle of Hell reserved for traitors. I hate her.

Finally, one thing I think is done really well is portraying how the girls think and feel when they’re younger. That struck me as superbly authentic.

Good job, Muriel. I might read The Girls of Slender Means too.

The Verdict

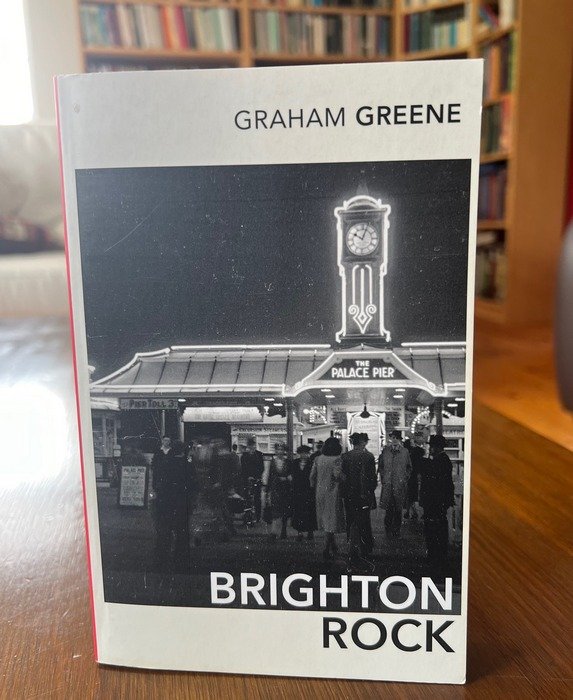

Hey, don’t neglect this classic.

OK, calling it a classic might be a bit premature. But I reckon that my book is a pretty good read – for the right sort of person!

The Best Nuisance I Can Be is a novelisation of my real 1984-85 college diaries. It covers my tumultuous final year as an undergraduate at an English university, a period that delivered friendship, love, oodles of fun and some horrible self-discoveries.